The Signature: A Brief History

Does that signature look odd or funny to you? Surprisingly, it’s Jacob J. Lew’s signature, Director of the Office of Management and Budget under Barack Obama’s presidency in 2011. Signatures are fascinating, especially when important figures, artists, leaders or business people draw them. Usually a signature isn’t comparable to one’s writing: a signature reflects one’s unique personality and legal importance.

Indeed, signatures are important and require codification. They can be falsified to appropriate money, goods and services. Through its evolution, one can learn about society’s progress from Antiquity to our modern era. This article, the first of a series, presents you with a brief history of the signature as an authentication tool.

Founder of Apple Steve Jobs’ signature.

Founder of Apple Steve Jobs’ signature.

A signature is a handwritten symbol put on a document, a piece of paper, or other material that allows authenticating someone’s identity and consent. It can take the form of a personalized drawing or a simple mark like an “X”. A signature is the certainty of someone’s agreement or consent concerning, for example, a contract of employment, a sales agreement, or one’s identity in simple letters. Everyone can sign, and the signatory (that’s the term) can be literate, illiterate, able or disabled.

During Antiquity, someone’s identity was verified through witnesses or by appending a seal on documents. The Sumerians and Egyptians used pictographs to convey meaning. The earliest relic we know of using words and symbols to validate identity is a Sumerian clay tablet dated back to 3100 BC. It displays marks from a scribe, Gar Ama, on which he made a list of 41 common professions.

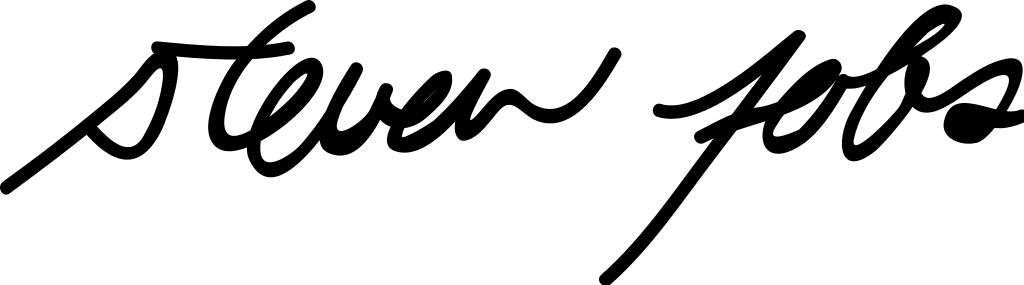

During the Middle-Ages, people could append marks or symbols on contracts and letters. Most of the time, these symbols were simple crosses, mere pictographs. It is not until the second half of the 11th century that we have knowledge of a document signed in the Latin alphabet. This signature was from Spanish military leader El Cid who made a donation to the Cathedral of Valencia.

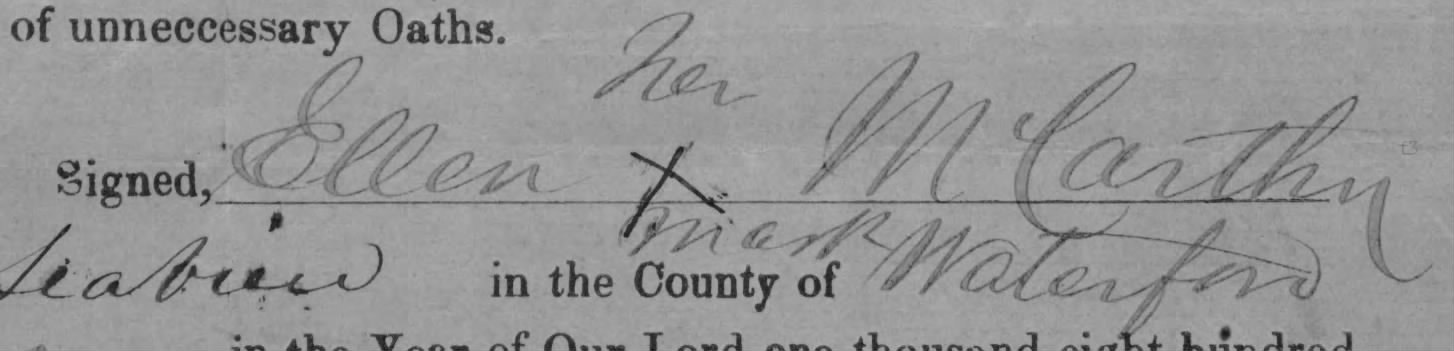

The donation to the Cathedral of Valencia on which is appended El Cid’s signature (In Latin, _Ego ruderico_ means _I, Rodrigo_, his actual first name). Open the link to zoom on the document and look for the signature on the right side of the last sentence.

The donation to the Cathedral of Valencia on which is appended El Cid’s signature (In Latin, _Ego ruderico_ means _I, Rodrigo_, his actual first name). Open the link to zoom on the document and look for the signature on the right side of the last sentence.

Some signatures that seem evident today, such as an artist signing its work, didn’t appear until later. In the Medieval Period, painters considered themselves craftsmen and weren’t particularly interested in posterity. Signatures had a down-to-earth role, such as mason’s marks (you can still see them on old stonework in Europe), which allowed masons to be paid for their work. Around the Renaissance, artists’ signatures started to be more common, such as the engraved signature of the now-famous Michel-Angelo on La Pietà, today housed in St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City.

On the statue, the artist wrote “MICHAEL ANGELUS BONAROTUS FLORENTINUS FACIEBAT”, which means “Michelangelo Buonarroti the Florezian did it.”

On the statue, the artist wrote “MICHAEL ANGELUS BONAROTUS FLORENTINUS FACIEBAT”, which means “Michelangelo Buonarroti the Florezian did it.”

The signature’s usage grew in Europe, and in 1677, its legal dimension was born. That year, the English Parliament voted the Statute of Fraud Acts requiring that wills, contracts, and grants should be written and signed to avoid fraud. We consider this Act to confer to the signature the importance it has now for the English-speaking world, at least.

As electricity was discovered and electronic tools appeared, signing automatically with mechanisms helped append one’s identity on a large number of documents. The autopen, which first models date back to the early 19th century, is still nowadays broadly appreciated by State and business leaders. Electronic arms hold and move a pen to give the signature an authenticated feel. This mechanical process, although handy, led to some polemics like the signing of the 2011 Patriot Act under Barack Obama’s presidency.

In today’s world, where digital tools are omnipresent, signatures can be found at the bottom of digital correspondences, being emails, where the name, forename, profession, address and other elements appear in text format and end the text. Sometimes the actual drawn signatures appear to convey a more formal intention. It is important to note that today an email can have legal importance without the personalized signature’s actual presence and can be used by a plaintiff or defendant.

To avoid falsification, numerous countries ask for the signatory to apply their signature in the presence of witnesses or a notary public to reinforce its legal character. On some legal documents, illiterate people can sign with a simple mark like an “X” as long as a literate witness also signs the document. In some countries, illiterates can append their thumbprint as a signature.

This picture shows the Irish illiterate emigrant Ellen McCarthy’s “X” mark on a pension fund demand paper in 1864. According to the Irish American Civil War website, she is part of the women “who lost a husband or son serving with the 61st New York Infantry. [...] The woman in question was seeking to prove her relationship with the soldier [...]”. This archive comes from the Widows and Dependent Pension Files from the American Civil War.

This picture shows the Irish illiterate emigrant Ellen McCarthy’s “X” mark on a pension fund demand paper in 1864. According to the Irish American Civil War website, she is part of the women “who lost a husband or son serving with the 61st New York Infantry. [...] The woman in question was seeking to prove her relationship with the soldier [...]”. This archive comes from the Widows and Dependent Pension Files from the American Civil War.

People with disabilities can also sign their identity on legal documents with the aid of a notary public, a typist, by power of attorney (a legal document giving one person the ability to act for another person) or physical guidance (help from someone to allow a disabled signatory to perform a movement or action). Signing can therefore be done by everyone and sometimes in numerous ways. Legislation can be quite flexible in some countries like the United States where, if no signing method is required, one can sign in any number of ways.

The notion and importance of signature vary between countries, writing systems, and applications. Nowadays, signing digitally is commonplace: this led us to build Genius Sign, a mobile app that allows you to sign any document of your professional and personal life quickly and anywhere.